Dr. Gary Garner

Director of Bands of West Texas A&M University 1963-2002

The WT Band Alumni are extremely pleased to honor and showcase our beloved Dr. Gary Garner. We believe his developing story speaks for itself and we all look forward to creating many more years of stories, memories and fun along side him. If we can keep up…

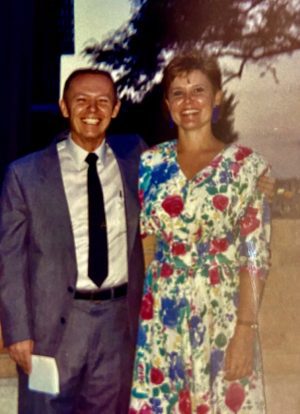

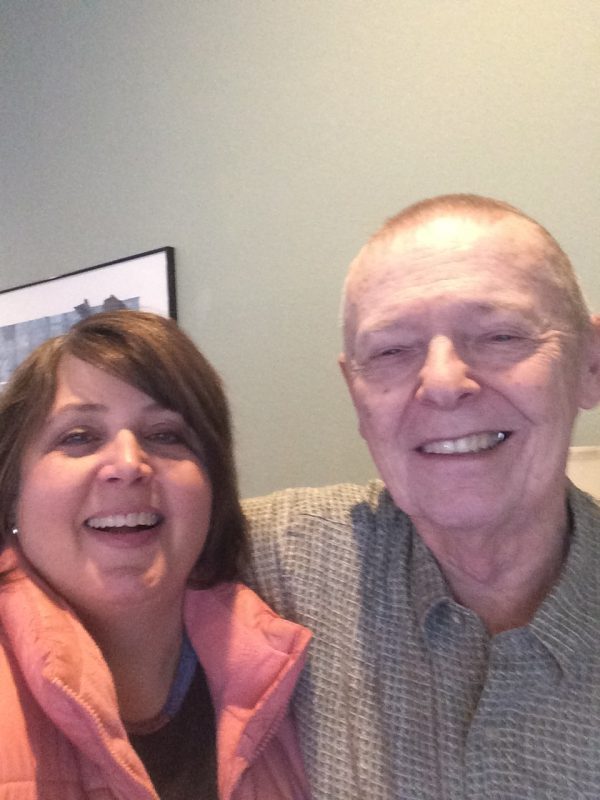

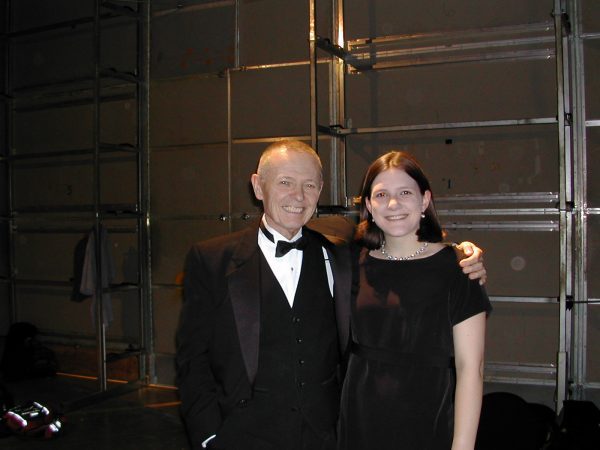

Gary Garner and Mariellen Griffin were married in 1951 and had 3 wonderful sons, Brad, Bryan, and Blair.

These are their tributes.

"For as long as I can remember, claims have been made about music in an attempt to justify its inclusion in the school curriculum. I have heard that it's a good tool for public relations and develops teamwork, good citizenship, good health, a good work ethic, and leadership skills, just to name a few. These may all be true, but it is possible to do those things just as well and for less money than with band. As I see it, humans have only one thing that separates us from everything else: music. Every major civilization has recognized the importance of music, and we are in the business of making it a significant part of our students' lives now and throughout their lives. I see it as a constant, immune to the passing of time and fancy."

- Dr. Gary Garner, The Instrumentalist, November 2006

We are greatly indebted to Russ Teweleit for allowing us to use portions of his 2006 Doctoral Dissertation to tell the story of Dr. Garner.

Read the story of Dr Garner as told by Russell Teweleit

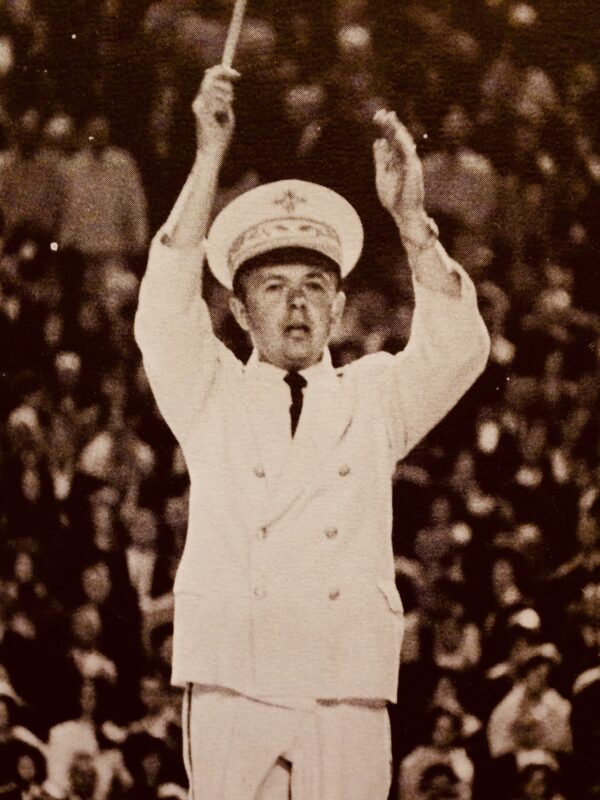

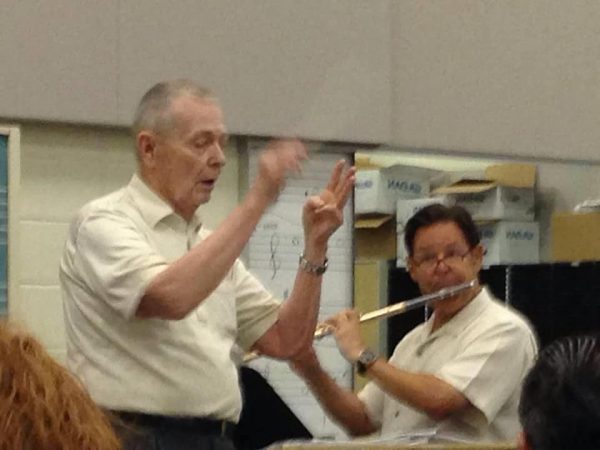

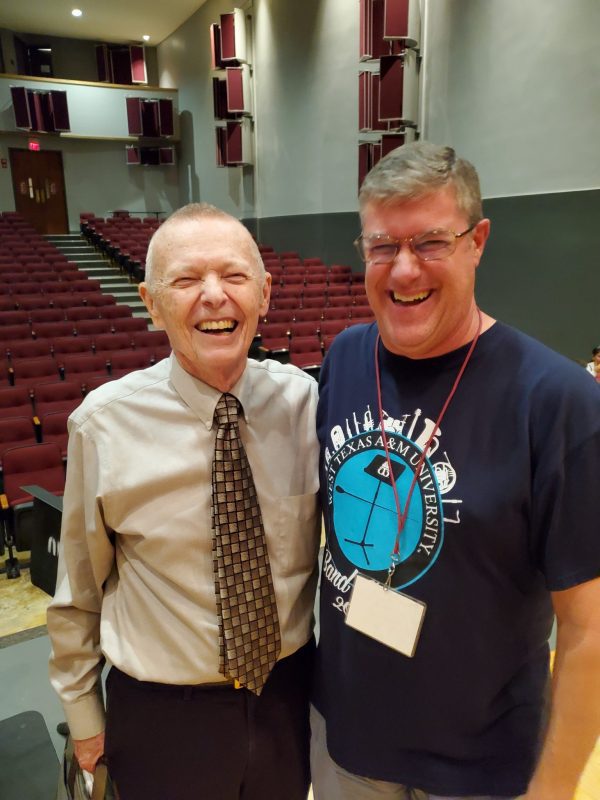

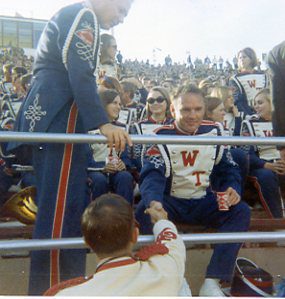

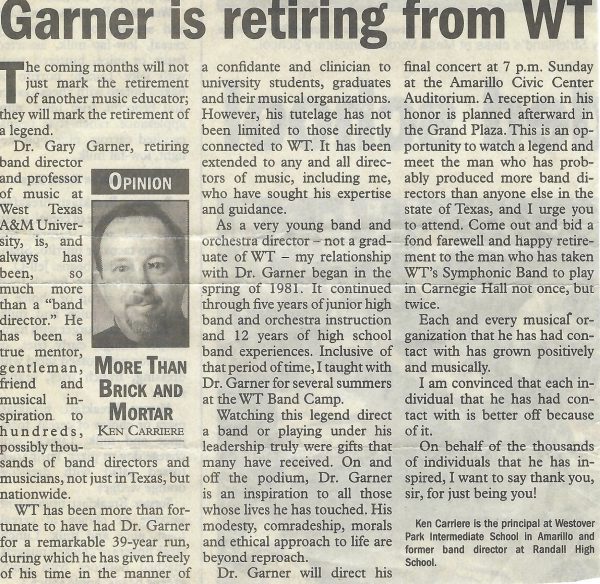

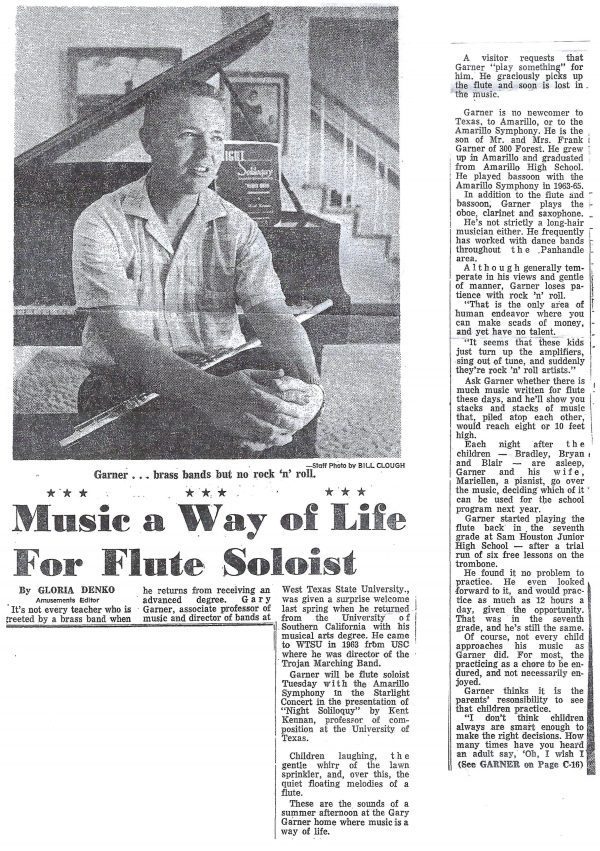

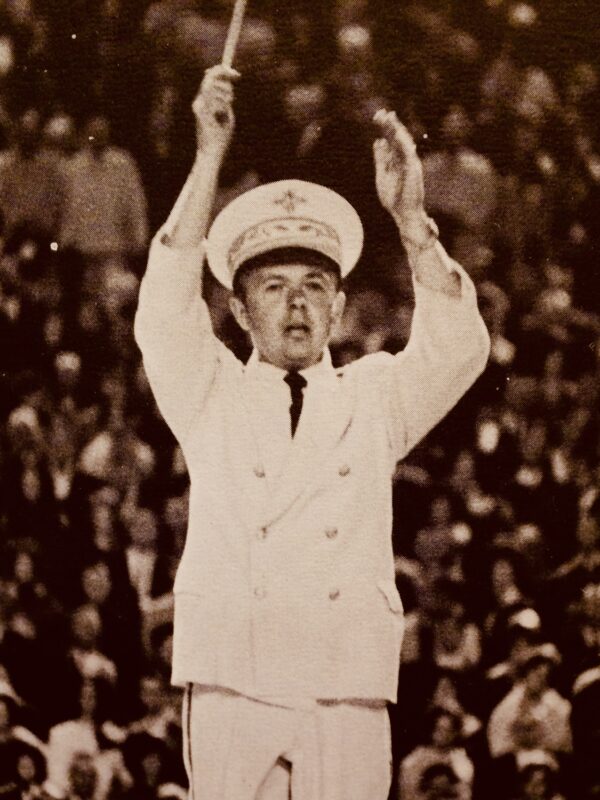

Gary Garner is arguably among the leading figures in the state of Texas and the band movement during the late 20th and into the early 21st Centuries. In addition to being the Director of Bands, Garner taught applied flute lessons, conducting, marching band techniques, and served as the Orchestra director during his thirty-nine year appointment as Director of Bands at West Texas A&M University.

Gary Thomas Garner was born on August 14, 1930 in Dodge City, Kansas to Benjamin Franklin and Madge Olive Garner. Garner’s father went by Frank although his brothers and sisters called him by his nickname, “Bill”, for reasons unknown. Frank Garner was a businessman. Early in his career Frank Garner worked for banks and then later moved into sales. Garner’s mother’s maiden name was Madge Irma Easley. She did not care for her given middle name of Irma and changed it, although not legally, to Olive. When Garner was eight years old his family moved to Amarillo, Texas. His father worked for the First National Bank and then later became a roofing salesman and a siding salesman. Garner’s mother was a homemaker until World War II when there was a shortage of men to do the work. She worked at the Amarillo Helium Plant before working in the payroll department at the Amarillo Air Force Base. Neither of his parents had extensive training in music, but Garner states:

"My dad played some piano, and I think he was actually very musical. I’m not even sure whether he took piano lessons or not. I think he might have taken some when he was a young man, but he loved nothing more than to sit down at the piano—and we never owned one—and play Pretty Red Wing or Listen To The Mockingbird. My mother used to sing. I think she might have been rather musical too. She sang around the house all the time, but that was about the extent of it."

Garner describes his becoming a musician as entirely accidental. His first formal musical training occurred in the fifth grade as a student at Margaret Wills Elementary in Amarillo. It was then that he took six weeks of trombone lessons. He states:

"There was a fella from Myers Music Mart that came to talk to our music class offering the use of a trombone and six free trombone lessons to anybody that wanted to do that. Then after the lessons were over, you had to start paying for the lessons and for the instruments. And so, I and... three or four other boys in the class volunteered to do that. All I remember about that experience, really, is that the first thing he taught us was the C scale [laugh]. We started in sixth position. I don’t know how I ever reached sixth position—actually I doubt that I ever did. Then I remember that after the six weeks ended telling my dad, “Well it’s time to buy the trombone now.” He said, “Now, are you sure this is really what you want to do?”, and I said, “Well no, I’m not sure.” And he said, “Well unless you’re sure, I don’t think we ought to invest in it,” which suited me fine—so that was the end of that."

As a seventh grader at Sam Houston Junior High, he had no intention to sign up for band. He recalls:

"It didn’t even occur to me to do it."

Garner did change his mind and joined the band at Sam Houston Junior High, however, becoming a musician and learning about music was likely not even a consideration in this decision. On becoming involved in music, he states:

“It had nothing to do with an aching desire on my part to become a musician."

Garner remembers:

“My two best friends were Dick Brooks and Benny Bruckner—both of whom still live in Amarillo—were in band; however, I guess they must have had about thirty beginners because all of the beginning band students were scheduled in the same classes all day long. And Dick and Benny said, “Hey, you need to sign up for band so we can be in the same classes” and I said, “OK.” So I went to see the band director. Charles Eads was his name, and I said, “Do you have something I could play and could I get in the band?” He said, “Well the only instrument we have left is a baritone saxophone.” So I said, “OK.”

Mr. Eads was actually a choir director. Garner explains that this was during World War II, a time when it was hard to find male teachers and most band directors were male teachers. Although he first began playing the baritone saxophone, he quickly switched to a much more portable instrument, the flute. He tells:

“I would take it [baritone saxophone] home to practice. It was just rather difficult because I always rode my bike to school. And, I don’t know, we probably lived a mile and a half or so from school. But with that big old bari-sax and especially a little kid, which I was [laughing]…it was very difficult and I would have multiple wrecks nearly every day.”

He soon gave up on taking the instrument home to practice and was not making much progress. Garner remembers:

“This is kind of amazing when I reflect on it, but it did happen. He [Mr. Eads] said, “Unless you start practicing, I’m going to take the instrument back and you can’t be in band anymore.” Well I was fairly committed to the idea of being in band, at that point, but I could see that the baritone sax was a non-starter for me.

So I went home and told my Dad that I needed to play something else and portability was the number one priority on my list. He said, “Ok, what do you want to play?” And I said, “I’m not sure. Let me look around tomorrow, and I’ll let you know after school.” You know, I’ll get back to you on that. So I looked around and of course the smallest thing I saw was the flute. I went home and said, “I want to play the flute.”

So he took me down to Tolzein Music Company, which was then down on Polk Street next to the old Paramount Theater, and we bought a Conn flute. I can remember being very excited about it. But I also remember going to bed that night and my mother came in and said good night and I was kind of crying I think. And she said, “What’s wrong?” And I said, “Mama”—that flute looked so overwhelming and complicated to me with all those keys. I said, “I’ll never learn where to put my fingers.”

Garner liked playing the flute instantly and experienced immediate success. He also signed up for flute lessons with Hall Axtell. However, he would only take lessons for about two years. He explains:

“Much of what I learned was wrong, but I suppose all things considered, it was still a helpful experience”

Mr. Eads was Garner’s director for his first year of band only. Clyde Rowe was Garner’s director beginning in the eighth grade and continuing through high school. Garner describes him:

“Clyde Rowe became the band director at Sam Houston and at Amarillo High School. So I had Mr. Rowe for five years—eighth and ninth grade at Sam Houston and all three years of high school. He was like a second father to me. I just thought the world of him. He, like others of his generation, was not trained to be a band director. You know at that time you didn’t go to school and study music education. The band directors, at that time, were people that had had some kind of musical experience whether they played an instrument in college, maybe played an instrument in the military and were certified to teach math, science, English, whatever. Mr. Rowe was really certified to teach math and of course in the early, very early days, I think this was perhaps earlier than his time, band was not a part—any kind of instrumental music—was not a part of the school day. They’d meet in the boiler room you know before and after school with anybody who could play an instrument. But anyway, band directors were not trained to be band directors and Mr. Rowe had played clarinet in the Hardin Simmons Cowboy Band and that was sort of his entrée into the band directing business. So, you know by today’s standards, his skills as a band director were limited. But…I have the greatest admiration to all of the people that were teaching band at that time—instrumental music of any kind—because they were by and large just making it up as they went along. So, as I said, by today’s standards he probably would not have been much of a band director, but judged by the standards at the time, he did just fine. More than that, he was a wonderful person and I revere his memory.”

As a flutist, Garner progressed quickly and played in the Amarillo Symphony throughout high school. He states:

“I guess maybe all three years of high school I was first flute in the Amarillo Symphony, although it wasn’t nearly the orchestra then that it is now.”

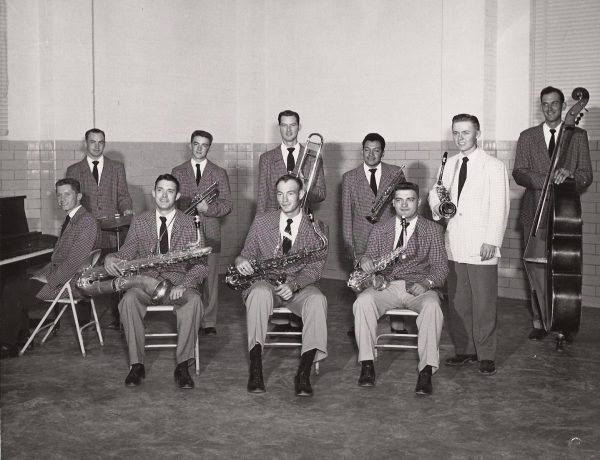

As a high school student, he also learned to play the clarinet and saxophone and promptly began playing in local dance bands. He remembers:

“Yeah, at that point now, as I said, somehow flute seemed to come rather naturally to me. I was doing well with it and attracted a certain amount of notoriety I guess as a flute player. But my friend Paul Mathis—a year ahead of me in school—Paul had a kid dance band as they were known in those days, and I remember them playing an assembly program at Sam Houston and they played Stormy Weather. I just salivated at the thought of being in that band. I wanted so desperately to be able to do that but of course it didn’t have any flutes.”

In or about his sophomore year in high school he convinced his dad to buy him a saxophone. Garner recalls his father bought him a Buescher Aristocrat alto saxophone with a Brillhart 3-star mouthpiece. Gordon Creamer, a friend of his father and a good saxophone player who played in bands around town, gave him some lessons. Garner states:

“Paul let me come over and sit in with his band at his house on 120 Wayside Street”

He further comments:

“Oh I, I thought that was just a glorious experience. I remember he [Paul Mathis] called me aside after it was over and he said, as tactfully as he could, “Uh…Gary…you don’t have to tongue everything.” Because I think I was going [singing Chattanooga Choo Choo] “ta, ta taah, tuh ta ta ta ta tum” [laugh].

The day he got his saxophone he recalls that he figured out the fingerings pretty much immediately.

“I thought wow this is so great and I played that saxophone probably on a Saturday—all day long. I didn’t know how to form a proper embouchure. I used a double embouchure—you know with the top lip over the teeth, probably biting way too hard, and I cut ridges both in the upper and lower lip—but I was just having a wonderful time. So after probably eight or more hours of practicing and honking on the saxophone that day I thought, well, before I go to bed I’m going to get out my trusty old flute and play a little bit on that. So I got out the flute and my lips were so swollen, I couldn’t get a sound. Not a sound. And that was incredibly upsetting to me and I remember crying and telling my dad, “Take it back, take it back, I don’t want to play it…I’m not going to be a saxophone player.” And he said, “Now well, just take it easy. Let’s wait and see how it is tomorrow.” Well by the next morning, the swelling had gone down and I could play the flute again.”

Garner kept the saxophone and did get a job playing in a little dance band. Many of the saxophone parts had clarinet parts too—so he bought himself a clarinet next. He went down to the Amarillo Band House and bought an old metal clarinet for around thirty dollars. He describes the clarinet as having a very definite bow in it— as if someone had sat on it.

He states:

“I must have had a fingering chart or something, but I remember being very confused by that register key because what was F in one register was C in the next.”

However, he soon overcame the confusion and tells:

“I got enough better that I started getting some jobs with some serious bands. But I was still…pretty serious about the flute at the time, practicing a lot and became increasingly absorbed with music.”

Following high school graduation, Garner, determined to avoid majoring in music because he feared that it would inevitably result in a career in teaching, enrolled at Texas Tech University as a geology major. The route in which he came to this decision is quite interesting. Originally, he had planned to attend North Texas. Several of his friends that had graduated before him in school were already enrolled there. Garner had already gone to visit the school, auditioned for the flute teacher George Morey, and visited with Claude Lakey who was the leader of the jazz band at the time. However the summer before he went to North Texas, a conversation with fellow band member Roy Boger caused him to change his plans. That summer Garner had a job with a band out at the Club Victoria. He describes the conversation as follows:

“Roy was probably twenty-five or so at that time. Great guy. He was a really good trumpet player and terrific guy, and we became fast friends—and he was somebody I looked up to greatly. And so, this is the summer after I graduated from high school. At intermission one night Roy said, “Well hey—what are you gonna do next year? You’re out of high school now.” I said, “I’m going to North Texas and major in music.” And his brow furrowed. He said “Aw,” and shook his head. He said, “You don’t wanna do that.” I said, “I don’t?” “No,” he said. “You know I went to SMU as a music major. I didn’t like it. I and all my friends got out of music. I got into marketing. It's the best thing I ever did.” He said, “You, you need to major in something else.” It seems incredible that I could be this naïve, or anybody could be this naïve, but I was. I said, “Well gee Roy, what do you think I ought to do?” He thought about it a minute and said, “Geology. There’s a big need for geologists right now. You ought to major in geology.” And, amazingly, I said, “OK.” I was too embarrassed to admit to him I wasn’t quite sure what geology was.” I went down to the Potter County Library the next day—down on Taylor Street—and looked up geology in an encyclopedia.”

The decision to become a geology major eliminated the need to go to North Texas. He recalls:

“There was a guy named C.A. Rogers who used to have a band in Amarillo out at the Nat (historic Natatorium Night Club) and I played with C.A. He had moved to Lubbock and had a band at the Cotton Club there. He called me three or four times, trying to talk me into coming to Lubbock and play in his band. Well now that I was going to be a geology major—I learned that they had a geology department at Tech—I had a ready-made job waiting for me there. Several of my friends were going to Tech. So I thought, heck, I’ll just go to Texas Tech, be a geology major, and play out at the…Cotton Club. So I did. And you know as stupid as that decision was, it was made even more stupid by the fact that I never was good at—and hated—math and science…and here I’m a geology major?!!”

Garner attests that he went to very few classes his freshman year. He states:

“I very quickly quit going to Chemistry, and Algebra, and German. [laughs] I had to take German.”

Geology quickly proved to be a poor choice and Garner eventually “became a music major by default.”

Following his first semester as a geology major, he states:

“I hated all of those [classes]. I was having a grand time playing my horn, though. So at the end of that first semester, I got my grades. I made an A in band! I even passed geology; I made a D in geology. I made a C in English and I failed Chemistry, Algebra, and German. So I had three F’s, a C, a D, and an A in band. And I got a letter from the dean saying, “I was not welcome to return to school that following semester”—which meant I would have to go home.”

However, a couple of his friends who were also playing in the C. A. Roger’s Band—Paul Lovett and Ted Crager—went to the dean and pleaded with him to allow Garner to stay in school. Garner describes the meeting:

“And the dean said, “Look, this kid failed nine hours.” I guess I really failed ten, because geology would have been a four…four-hour course. …“I can’t let him back in school.” But they…continued to implore him to let me come back to school and finally he relented and he said, “OK, I’ll let him come back on two conditions. First of all, he has to change majors.” [laughs] That was no problem. The last thing I wanted to be was a geology major. “And second, you guys have to promise you’ll get him out of bed and get him to school every morning.”

Garner’s failure to go to class had really caused him to dig quite a hole for himself. He explains that if you cut class enough you would be assessed negative hours. He had cut class over ninety times and amassed three or four negative hours in that first semester. He states:

“You talk about going backwards in a college career. I was way ahead when I set foot on the campus beyond what I was at the end of that first semester.”

And tells:

"That’s when I became a music major by default. Now I had never, ever, ever, intended to be a teacher. I didn’t want that at all. That was at the very bottom of my list of possible careers, and the prospect of being a music major at Texas Tech was distinctly unappealing to me because that’s…all they had in fact they didn’t call them music ed majors, they were band majors. And a degree in music at Texas Tech automatically pointed me in that direction…which as I said was quite unappealing."

Nevertheless, Garner did become a music major. Following his change in majors Garner states:

“Those guys actually did come and get me out of bed and I didn’t fail anything else.”

Dr. Garner’s band director at Texas Tech University was D. O. Wiley, or Prof Wiley as the students referred to him. Prof Wiley had also taught Dr. Garner’s junior high and high school director, Mr. Rowe, in the Cowboy Band at Hardin Simmons.

While playing in the Texas Tech band, Garner met Mariellen Griffin, who would become his wife of forty-three years. Mariellen was a piano major but also played flute in the band. Garner continued his studies at Tech until midway through his third year of college when he joined the Air Force. At the time, he and Mariellen were anxious to get married. However, due to the Korean War he was certain that he was about to be drafted. If drafted, Garner felt there was no way to know where he would be stationed. He learned of an opening for a flute player in the Reese Air Force Band in Lubbock. He recalls:

“I went out there and played for the bandleader Mr. Luce. He gave me a letter, assuring me of being assigned to the band at Reese Air Force Base after I completed basic training.”

Joining the Air Force would ensure that he would stay in Lubbock and he and Mariellen could continue with their marriage plans. So, in January of 1951, he joined the Air Force, went to basic training, and returned to Lubbock. He and Mariellen were married the following July. He states:

“Well, the Air Force was not a really pleasant experience. I was in the band, of course. Mr. Luce, the guy that gave me the letter, had been transferred by the time I got there and then they got another bandleader that was roundly disliked by everybody in the band. Disliked is much too kind a word actually and I was among those. I mean there were no exceptions.”

Being stationed in Lubbock allowed Garner to make a good amount of money playing in dance bands with his old buddies. He states:

“But that was illegal at that time. The GIs were not supposed to play in civilian bands. So, that was all on the sly, and I was keeping a very well-guarded secret that I could play the saxophone.”

However his activities were eventually brought to the attention of the warrant officer. He tells:

“And my reward was getting put in charge of the dance band.”

He was also made the assistant leader of the band itself. At the time he was not at all happy with making less money and having increased duties. In retrospect, he came to realize—much later—that this provided him with valuable experience as he was doing a lot of arranging, rehearsing the dance band, rehearsing the concert band, and section rehearsals. He states:

“I also did a lot of practicing. Practicing was required, and of course, I loved doing that.”

Though, at the time, he still did not think he was going to become a band director.

After serving his three years in the Air Force, Garner went back to school at Texas Tech, this time married and more mature. However, he admits that he returned:

“Still not thinking I was going to be a band director —I don’t know what in the world I thought I would be—but I was certainly headed in that direction.”

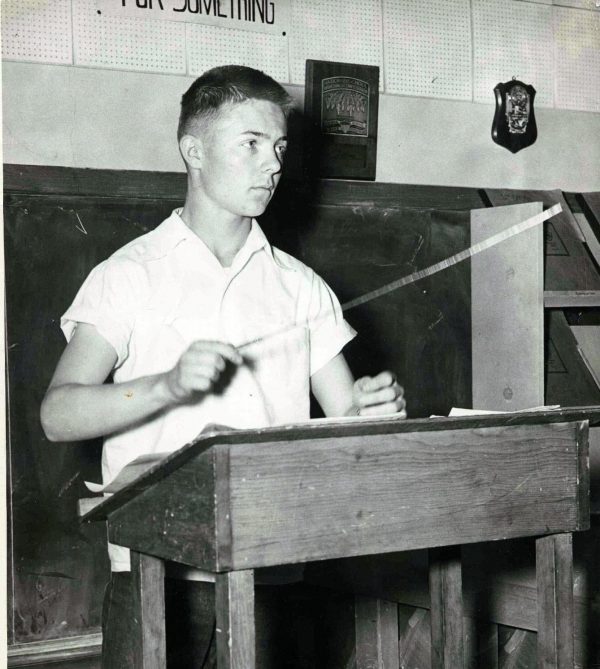

He soon found himself student teaching with his friend Ted Crager who was now teaching at Hutchinson Junior High School. Garner states:

“And I discovered to my utter astonishment, that this is something I really did like doing, and that’s the first time that I decided that I was going to be a band director.”

At the end of that year, Ted Crager was hired to be the band director at the new high school in town, Monterey High School. Crager pushed to have Garner hired as the director at Hutchinson, but the principal refused because Garner had not yet finished his degree. Instead, O.T. Ryan, who was teaching at a junior high in Plainview at the time, was hired. However, Garner tells that many in Plainview were very unhappy about the prospect of losing O.T. Ryan. He had done a wonderful job there and they “upped the ante quite a bit” to keep him in town. Then, very late in the summer, O.T. Ryan called Lubbock and backed out. This left Hutchinson without a band director not too long before school started.

Garner recalls:

“So, I remember I was in my garage one day, doing something or other, and Mr. Gordon—Jay Gordon, the principal at Hutchinson Junior High School—suddenly appeared in the doorway, and said, “Are you still interested in that band job at Hutchinson.” I said, “Oh yeah.” He said, “Well, we’d like to hire ya half-time, and then you can go to school the other half-day. Teach at Hutchinson a half day, and the other half day continue to work on completing your bachelor’s degree.” So, that’s what I did. It was a great stroke of good fortune, for me.”

As a half-time band director and half-time student Garner took his studies much more seriously and did very well from that point forward. The half-time position was in reality a full time job. Garner states:

“So, it was a busy year, but I loved it.”

He finished his degree in the summer of 1955 and then returned full time the next year to Hutchinson with the only addition to his schedule being study hall.

His teaching duties included two periods at Monterey High School, the bands at Hutchinson Junior High, and one or two study halls. He assisted Ted Crager with the Monterey Band during the first hour, and then he taught the Cadet Band at Monterey during the second hour.

He describes the Cadet Band as a “miserable little band. There probably weren’t fifteen people in there.”

At Hutchinson there were three bands, the A band, which was the performing group, the B band, which was the second band, and the C band, which was the beginning band. He states:

“And beginning band was just that. You had everybody in there. I had alto clarinets, and you know oboes and bassoons, and everything. You just taught them all at once. That’s just the way it was done.”

Garner would remain the director at Hutchinson Junior High for a total of four years. He states:

“It was great fun. I look back on those years with great fondness”

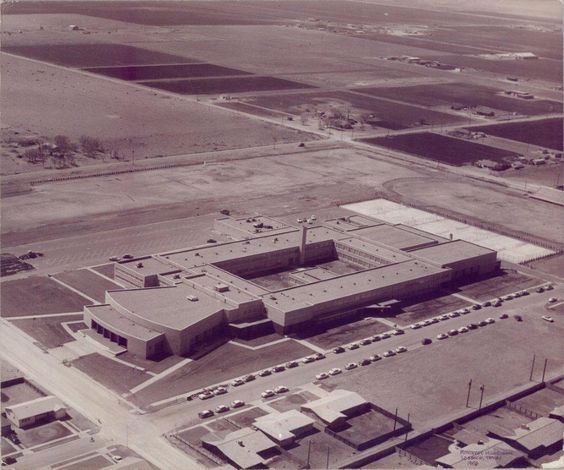

Garner spent four years as the director at Hutchinson Junior High, and the following year he was hired as the band director at Monterey High School in Lubbock—a position he would hold only for one year. Ted Crager had left to accept the job at West Texas State College (now WTAMU) in Canyon, Texas. Garner admits, “It might have been the most enjoyable year of my whole teaching career. It was wonderful. The kids were great! I’d had most of them in Junior High.” He adds:

“They played very well and I had the world’s best principal and the physical set up at Monterey was, at that time, state of the art—wonderful band room, practice rooms. It was heaven on earth and I only was responsible for three hours a day. I couldn’t believe that. I had the top band, then the cadet band, and one study hall. That was my teaching load. It was just glorious. It was just glorious!”

“I incorporated all that stuff into what we were doing with the marching band, which at that time—owing to Casavant—certainly not to me. If I could claim any credit for it, it was just by being lucky enough to see Casavant and to at least be half smart enough to know, boy this was the wave of the future. But anyway, it created something of a sensation.”

G.T. Gilligan, the band director at Kermit High School, asked Garner for a film of his marching band and he sent him one. He explains that Gilligan had been borrowing and sending marching films around. Apparently, Gilligan had been in contact with John Green who was the marching band director at USC and Gilligan had apparently sent his film there. Garner states:

“Well, John [Green] left that spring to go be the director of bands at Long Beach State, and Bill Schaefer who was the director of bands at USC had seen that Monterey Film and on the strength of that, he called me.”

Interestingly, John Green would eventually serve as Garner’s department head at West Texas State University (now WTAMU). Garner describes the phone call as a “bolt out of the blue.” He states:

“It was a huge shock to me. He [Schaefer] said, “Well let us fly you out here, and talk about this marching band job.” And, you know I was very flattered and excited about it, but also, not at all eager to leave Monterey. But anyway, I did. I flew out there, and talked to them and they offered me the job. And I came home, still a little bit undecided. It just seemed like such an amazing opportunity, and my wife was really anxious to do it. So, with a heavy heart, I resigned at Monterey and went to USC.”

Garner spent the next four years at the University of Southern California teaching and pursuing his masters and doctorate degrees. He states:

“The four years were good in some ways—great in some ways—and then really bad in others. I loved the kids in the band.”

At this point he had begun a masters at Texas Tech and had accumulated approximately 17 hours.

At Texas Tech most of his graduate hours were non-music classes, but he did have some music classes. He took clarinet lessons and conducting with Keith McCarty who he describes as a conscientious teacher and very competent musician. Garner states, “Conducting was not really his particular field of expertise, but I can’t say that the class was without value.”

Other courses that Garner enrolled in while at USC include Analytical Techniques, Community Orchestra, Concert Music, and Band Arranging. Analytical Techniques was essentially form and analysis. There were not enough enrolled in the class for the class to make, so he studied privately with Ellis Kohs. He found this to be a very useful class. The Concert Music course involved attending concerts in the Los Angeles area. He recalls:

“I remember hearing one of them was West Side Story, which had just come to L.A. And also, two concerts at Hollywood Bowl with the L.A. Phil, one of which was conducted by Herbert von Karajan and another by Andre’ Cluytens, the great French conductor.”

Garner studied Band Arranging with Bill Schaeffer, the director of bands. During this semester, Garner arranged a movement of the Prokofiev Fifth Symphony.

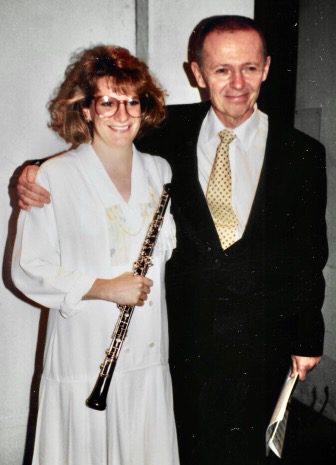

Among the most valuable of Garner’s experiences at USC were the applied lessons in which he enrolled. While there he took a couple of semesters of bassoon with Ray Nowlin, three semesters of oboe with Bill Criss who had spent ten years as principal oboe with the New York Met and was working as a studio musician in Los Angeles, and one semester of flute with Roger Stevens.

Doctoral students were required to have four fields of study: a principal field, which in Garner’s case was Music Education; music history, which was required for all candidates; for his third field, Garner chose band arranging; and a craft field. The craft field was essentially an elective and Garner chose to do woodwind performance. He states that he studied the woodwind instruments for his own edification and it just turned out that it also fulfilled the need for a fourth field.

As a faculty member at USC, according to policy, Garner was only permitted to enroll in one course each long semester. In the summers he would take as many courses as possible. Fortunately, possibly because he was a faculty member, all of his hours from Texas Tech transferred. He finished his Master’s in 1962 and immediately proceeded with work on his doctorate in the spring semester of 1963.

His job with the marching band was quite challenging and the teaching situation was in many ways less than ideal. It was an all-male band, as women were not allowed in the band at that time. He explains that the band performed a different pre-game and half-time show at each game. The rehearsals took place on Thursday and Friday afternoons from 3:30 to 5:00 at Cromwell Field. It seems unthinkable, but the marching band also had to share the field with the freshman football team during each rehearsal. To make matters worse, about a third of the band would have labs on Thursday and another third on Friday. He states, “So there I was trying to do two brand new shows with two-thirds of the band at a time, with three hours of rehearsal.” Adding, “The only time we’d have the full band and the use of an entire field would be at the performance.” He continues, “You can just guess what an impossible challenge that is. So that was enormously frustrating. And, oh my gosh, I dreamed about Texas that whole time and about Monterey High School.” In addition to the marching band, Garner had a very small concert band. It was made up of the students that either could not make the top group or were not interested in it. He states:

“So, we had a dozen or so kids in there, but I really didn’t want to… make my career as a marching band director.”

Then, after about a year at USC, Mr. Honey, the principal back at Monterey High School in Lubbock, called to inform him that they wanted Garner to come back. Fred Stockdale who had followed Garner stayed a year and then left to teach in Pampa, Texas. Garner describes:

“I never wanted to say yes to anything so much in my life, but I thought it would just be too embarrassing. Because I’d gone out with such fanfare, you know. Made the big time and I felt as if I’d be sort of be coming home with my tail between my legs. So, I did say no, but it turned out to be a good thing.”

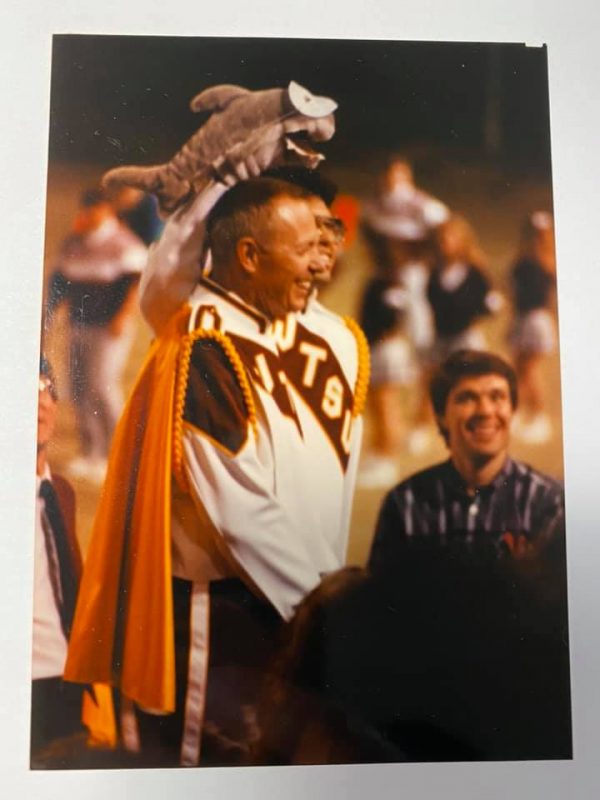

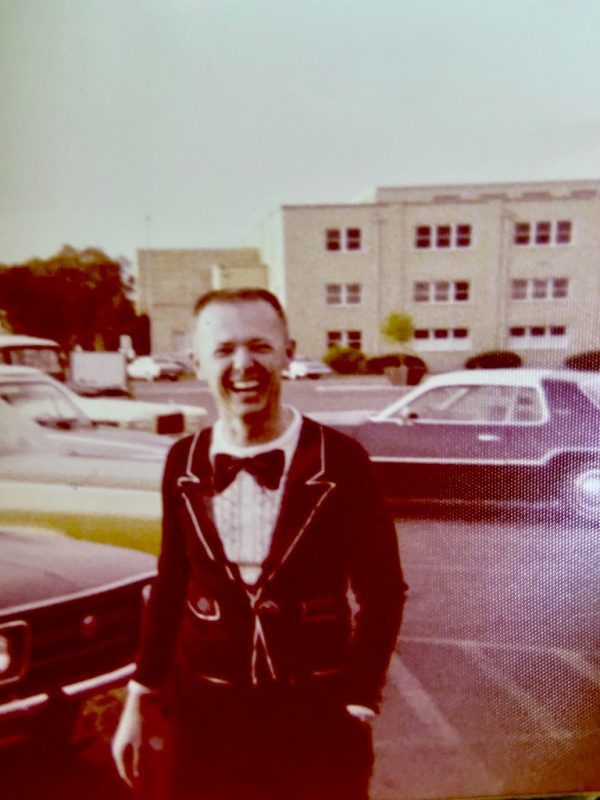

After four years at the University of Southern California, Garner joined the faculty of West Texas A&M University (then West Texas State University) as Director of Bands in 1963. Garner would spend the remainder of his 48-year career at WTAMU. His time as the WTAMU Director of Bands would span thirty-nine years from 1963 until his retirement in 2002. Just as Garner followed his friend and mentor Ted Crager in the only two jobs (Hutchinson Junior High and Monterey High School) he had held before USC, he would once again follow him at WTSU. Ted Crager was the department head and band director at WTSU and he had told Garner right from the very beginning that he wanted to give up the band to be full time department head and hire Garner as the band director. At first, Garner had very little interest in the job. He states:

“I just sort of thought of WT as just a little cowboy school down there in Canyon. But, after some considerable frustrations with the SC thing, WT became increasingly more attractive to me. So, I did take the job after four years at SC.”

However, Ted Crager actually left WT before Garner began his first year. Matilda Gaume, who was the music history professor, was made acting department head until a new department head could be hired. He recalls:

“I was so concerned about that. I had the temerity to call Dr. Cornette the then president and give him three names of people I thought would be a good department head.”

Garner thought it even more amazing that Dr. Cornette actually contacted the candidates that Garner had listed. He recommended Justin Gray, who was the band director then at the University of Wyoming. Gray had been at USC working on a degree and also had a lot of administrative experience. Garner says of Gray:

“A good guy and I thought he’d be a terrific department head.”

The second name that Garner gave was that of Brandon Mehrle. He was the Assistant Dean of the School of Music at USC. Garner states that:

“He was a great guy, (he) would’ve been a wonderful department head.”

The third person that Garner listed was John Green. Green was the department head and band director at Long Beach State. Dr. Cornette contacted all three individuals. Ultimately Gray and Merla were not interested; however, John Green was. He accepted the position and began the job in January of 1964. Incidentally, Green would eventually become the Dean of Fine Arts at WT.

At this point, Garner had finished everything on his doctorate except one summer of coursework, qualifying exams, a language exam, and his dissertation. The following summer (1964) he took his family to California with him. They stayed in married housing and he completed his remaining coursework. Of that summer he states:

“Gosh, that was a miserable summer. I mean it was just such hard work. One of the courses I took was a course in…early music notation, which I had no interest in and no need for really but I needed an elective and that was what was offered.”

Early music notation was taught by Dr. Carl Parrish, the same professor that Dr. Garner had earlier for a semester of Renaissance Music. He describes, “This notation course was just an absolute killer. I was studying that 8 and 10 hours a day. I think I still made a B.”

The following summer (1965) Garner went to USC by himself in order to prepare for and take the qualifying exams.

He describes the qualifying exams as a huge hurdle and states:

“I took a room at a fraternity house and studied literally day and night. I took the qualifying exams, passed those. Boy once you get past that, you’ve got it made.”

Next, Garner had to focus his attention on the language exam. The choices were French or German and he had never studied a foreign language of any sort. That is, unless you count the semester of German that he failed during his freshman year at Texas Tech. He states:

“All I knew was Bleistift—pencil. That wasn’t enough to get me by however at SC. So, I was told that if you didn’t know anything of either one that probably French was the easier route to go.”

The exam only required a reading knowledge of the language and not an ability to speak it. Garner selected French. He then went to the head of the French department to ask if he could possibly take the French exam at home, in Canyon.

He recalls this as one of the luckiest things that happened to him and states:

“I don’t think ordinarily they would ever allow you to do that, but he was leaving. He was very angry about something. He said, “Yeah, go ahead that’s fine.” [laughs] He didn’t care. So, the arrangement was, I was going to go home and study French.”

It was then arranged for Ples Harper, who was the head of the language department at WTSU, to administer the exam. With the arrangement to take the exam in Canyon approved Garner next needed to select a book for approval. He chose Schoenberg and His School: The Contemporary Stage of the Language of Music by René Leibowitz (1949). He states, “The reason I chose it was because there was an English translation of it [Translated from the French by Dika Newlin].” The exam consisted of being given a starting point to be selected on the day of the exam and translating for three hours.

In preparation for the French exam Garner took a few French lessons from one of the French professors at WTSU and he states:

“That next year, I just flew by the seat of my pants on the job. That’s all I did, was study French and I’d just go into rehearsals and wing it. I shouldn’t have been paid a cent for that year, but it was either that or just not see this thing through. I couldn’t do both.”

Garner studied constantly and practically memorized the book, and by the time he got to the point of taking the test, he sat down and wrote furiously for three hours. He had prepared so vigorously that the exam was not a problem. He states:

“I passed that with flying colors and, of course, proceeded to forget about everything I learned, but that wasn’t the point. The point was just jumping through that particular hoop, you know, one more hurdle to be overcome on the way to the completion of the degree.”

With the language exam out of the way, the only thing that remained was a dissertation. The dissertation topic involved trying to achieve an historical balance in band performance. He tells:

“At that time, there were no transcriptions, nothing from the 16th or 17th century. There’s a lot now. So, I found a ton of music—instrumental music—that I arranged for band and that was the thesis.”

Following the completion of his dissertation he went one more time to USC to defend his dissertation in the spring of 1967. He describes this as a huge burden lifted off his shoulders. Of the doctoral process, Garner states:

“More than anything else, I think it’s just an exercise in tenacity.”

Garner’s duties in his earlier years at WTSU amounted to an enormous teaching load and included:

“Everything except sweepin’ up—and I think I did that too.”

In his first year he taught the marching band, band, stage band, music appreciation, methods, flute, oboe, saxophone, and bassoon. He explains:

“It was concert band that I was interested in so, that was a welcome change and there were a few really terrific players in the band”

There were 96 in the band his first year, 120 the next, and the peak occurred sometime in the early eighties with over 240 in the band. He explains:

“The teaching load was just oppressive, but I didn’t mind it. I just loved it so much.”

He recalls that three of the superstars in the band during his first year at WTSU were Darrell Garrison, Lynn McLarty, and Gerald Grant. Darrell Garrison was a freshman horn major, from Guymon, Oklahoma, Lynn McLarty was a clarinet player from Seymour, Texas, and Gerald Grant was from Petersburg, Texas. Grant later became lead trumpet at the Stardust Hotel in Las Vegas for several years.

In addition to the few superstars he describes that the rest of the band consisted of, “a bunch of very decent players, and then a bunch of them that, you know, could hardly get the case open. So the spread of talent in that band was huge.”

By Garner’s third year, the band had grown enough to split to a Symphonic and a Concert Band. He recalls:

“There was a huge jump in the quality of the band then. Because…we had a select group, and the people down toward the bottom of the sections were far better than they had been before. And everybody’s needs were better met, including people in concert band. So, that was a big jump forward the day that we were able to do that.”

He states that WTSU was adding new faculty regularly along those years. He remembers:

“When I came, there were three wind faculty. Rowie Durden, Gerald Hemphill—the trumpet teacher, and Gerald was teaching all the brass and Rowie Durden. Rowie taught clarinet and percussion and I taught all the rest of the woodwinds. So there were three on the wind faculty then.”

Recruiting in those early years was certainly difficult. The majority of the students were from the panhandle or from small schools. There were, “no students to speak of from any of the big schools with red hot band programs.” He recalls:

“I couldn’t attract any blue chip players. You’d say West Texas to somebody in the All-State Band…you know if they were from a big school and they’d practically laugh in your face. So, I decided —and I think Rowie and Gerald felt that way too—that, if we were going to do anything significant, we just needed to get kids there and, then teach them how to play and, I think really that’s pretty much what we did.”

By Garner’s third year they were able to add a bassoon position and a low brass position. He states:

“That was a huge step forward. The low brass position was also to be an assistant band director.”

Don Baird applied for both positions and sent in tapes on bassoon and euphonium. Garner states that both tapes were very good, but obviously Don Baird could not fill both jobs. They had also received a superb bassoon tape from Don Munsell. Munsell was selected for the bassoon position and Don Baird, who had been the director of bands at Phillips University, took the position as low brass teacher and assistant band director. This gave Garner some help with the marching band and a person to conduct the concert band. That same year, 1965-1966, Gerald Hemphill left and Dave Ritter was hired as the trumpet teacher. After Dave Ritter had served on the faculty a couple of years, he expressed an interest in directing the jazz band.

Garner was more than happy to have him do that, and recalls:

“So, then I had somebody helping with marching band, doing concert band, somebody else doing the jazz band. That lightened up the load somewhat, it was still pretty heavy but it was decidedly better.”

The bands had also improved. He states that the 1966-67 band was the first “somewhat noteworthy” band he had. He took this band to Colorado Springs to perform at a southwestern division meeting of MENC. However, it was the 1967-68 band that he describes as the first “powerhouse” band and it was this band that provided Garner with some of his most memorable experiences as a director. The following year the band performed for the first time at the Texas Music Educators Association Convention. He states:

“The band, it created a small sensation, I think, at TMEA.”

Adding:

“One of the things we really had going for us was the element of surprise. ‘Cause most of the band directors in the state, didn’t know there was a West Texas State, much less that there was a band there, much less that it was half-way decent. And, I think they were just astonished by it.”

J.R. McEntyre was the band division chairman and up until that time it would be very rare for a college band to play at TMEA.

The WT Band was one of the first universities selected to perform at TMEA.

There were three concerts with one band performing at noon each day on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. He states:

“Well, J.R. and I are old friends so we got invited. And more than that, we got the choice spot which was Friday at the band director’s band division luncheon. They dropped that years ago, but that was the time of the band director’s luncheon. It was in Austin that year and the University of Texas had played on… Thursday. We played on Friday and then Sam Houston State, with Ralph Mills, which was a very fine band at that time, played on Saturday. And, I think if I could re-live one moment of my life, this would be the moment. ‘Cause after we finished playing, it seemed like the applause went on forever. Which was, [laughing] you know, wonderful. Finally, it started to die down and George Riddell, stood up on one of the tables—understand this was at a luncheon in a big hall there—and George stood up on a table and he announced the score at the top of his voice. People heard him yelling and it then got very quiet around there. He announced the score. He said, “West Texas State University!… 100!, University of Texas!… Zero! And the applause started up all over again. That’s the moment [laughs]… that I’d love to re-live.”

Adding:

“So, that was a great, great, great time, and a really good band. And of all those ten TMEA performances, I think it’s because it was the first performance. That, for me, was really a high point.”

He states that the band, “didn’t know anymore than I did whether people would laugh and jeer or throw things at you. We just didn’t know. We sure worked hard and they delivered. It’s a great moment.”

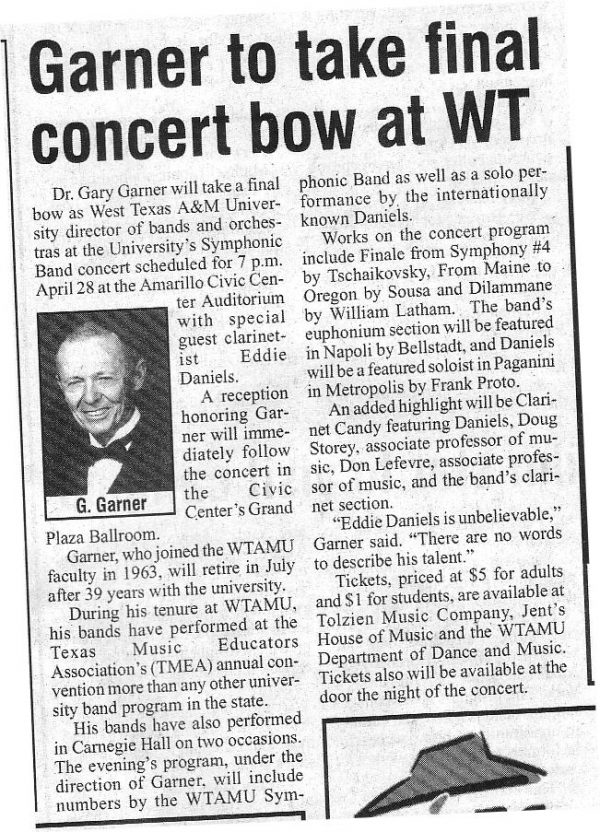

Following that performance, recruiting became infinitely easier. During his tenure, the WTAMU band performed twice at College Band Directors National Association (CBDNA), twice at Carnegie Hall, and was invited to perform at the Texas Music Educators Association (TMEA) annual convention a total of 10 times—more than any other university band in Texas. Garner cites the 1968 TMEA performance of the WTSU band as being his most memorable.

“People didn’t know we had a band here,” Garner said. “And as a band we didn’t know what to expect, but it was a smashing success. We felt as if we’d hit a home run”

Over the years the wind and percussion faculty at WTSU would grow from three to eleven. However, it always seems that whenever Garner’s load would be lightened by the addition of another faculty member, he would add something else that he previously did not have the time to do. For instance, in 1978 when Sally Turk was hired as the flute teacher, Garner promptly began conducting the orchestra. He recalls:

“At that time, I had twenty-five flute majors, plus doing a band and teaching a bunch of classes. And you know, with the marching band in those days, we were pretty much doing a different show every week. I was writing all the drill, writing most of the music…and…we’d probably do four, at least four shows a year, maybe five…. It was just overwhelming…. I really didn’t want to give up the flute. I loved the flute teaching, but I just was overwhelmed. I remember going to Harry Haines and telling him, “Hey, we need to hire a flute teacher.” So, he went and made his pitch, but they wouldn’t do it or couldn’t do it then, but the following year, they did. And then suddenly, I had a lot of time. And that also coincided with…an opening for an orchestra director, and I’d always kind of lusted after that. So...that’s when I became the orchestra director. I think we had [seven] string players that year. [laughs] That’s always been a hard job. I remember telling the orchestra kids, the string players, “We are going to go to TMEA before you graduate”, and I believed it. I thought I could do with them, what we’d done with the band, you know. It’s just, not the same. I think…25 or 6 string players…is the most I ever had.”

Of his first year as orchestra director, he recalls:

“We had three violins, two violas, a cello, and a bass. We had seven. We had seven string players. I still remember who every one of them was too.”

As director of the WTSU Orchestra, Garner worked hard to become more knowledgeable of string instruments. He states:

“And so, I took four years of private violin lessons in order to try to shore that up a little bit.”

Garner would serve as the orchestra director from the fall 1978 until his retirement. Upon adding the job to his schedule, Garner was faced with the challenge of recruiting string majors for an orchestra that, at that point, consisted of seven strings. In order to better recruit string players, he applied for and received a grant from the Don & Sybil Harrington Foundation in the amount of $500,000. This grant established the Harrington String Quartet. The idea behind this endowed quartet was that the members serve as part-time instructors at WTSU and also perform as the principal chairs in the Amarillo Symphony. The establishment was an invaluable achievement that continues to benefit the department today some twenty-four years later.

Throughout his career, Garner wrote numerous arrangements for band and marching band. However, he never attempted to have any of them published. Nearly all of his arrangements were utilitarian in purpose and written for a specific event, tour or concert. He tells:

“You know it’s not that I have a great interest in doing arrangements. I really don’t. I wouldn’t say I have no interest in it, but they’ve all been done for specific reasons”

He recalls:

“I heard Joy McCattern play the Gordon Jacob Oboe Concerto, this would have been back in the seventies probably, on seminar one day. I thought that was so great we’ve got to do that on tour.”

He then wrote a band arrangement of the third movement for Joy to play on tour. He explains that another time:

“Russ Blanchard came to me one time and said, “You featured other sections of the band on tour, but you’ve never featured the tuba section.” I said, “Well Russ, what would it be on?”, and he said, “On the first movement of the Gregson Tuba Concerto.” And I said, “Well is there a band arrangement?” He said, “No, but you could do one.” So, I did one and we wound up playing it at TMEA.”

As part of the agreement with the publisher Garner did have to send the Gregson arrangement to the publisher in England. He explains:

“That was part of the deal. OK, you can do this but send us a score and a recording. So, I did that and he wrote back and said Gregson thought the arrangement was OK and we’d like for you to do the other two movements of it and we’ll publish it. I never did do it. That’s as close as I ever got to publishing anything. I’ve just never…pursued that.”

In regards to written publications, Garner does have a few. Two of these were articles written for the Southwestern Musician, a publication of the Texas Music Educators Association. The first was on the flute and was written while he was teaching in Lubbock. The other was in 1987 when he was selected Bandmaster of the Year by the Texas Bandmasters Association. Following his acceptance speech, Bill Cormack the executive director of TMEA, contacted Garner and asked if the speech was written down because he had had a few comments on it and thought he would like to publish it in the Southwestern Musician. He remembers:

“Well, I didn’t have it written down, I mean, I had a few caption headings. So, I did write that speech to the best I could remember the principal points and they published that in the magazine.”

“Harry Haines came to me one time and said, “Hey we need to write a book together... Let’s write a book on directing band. We’ll get James Middleton to contribute to it too.” And I really had no interest in doing that, but I said OK.”

He describes the first draft they received from the publisher as being replete with misprints and recalls:

“They sent the galleys on it the first time through and, oh my gosh, it was awful and we sent them corrections. Sent it back and said please don’t publish this ‘till we see the next set of galleys and the next thing we saw was the published book—and there’s still a lot of misprints in there. Then a few years later, I don’t even know whose idea it was, we did a second edition of it, which is very much like the first edition, but it’s sort of new and improved a little bit. I never did like that first title. It was so long and cumbersome [The Symphonic Band Winds: A Quest For Perfection]. It was my son Bryan that suggested The Band Director’s Companion. So, that’s really the same book—just two different editions of the same book.”

Garners two chapters in The Band Directors Companion consist of one on the rehearsal and the other on intonation.

Garner also co-authored another book with Haines entitled T.R.I. – Technique, Rhythm, & Intonation (Haines, McEntyre, & Garner 2000). Garner’s involvement in the TRI came about when Harry Haines and J.R. McEntyre approached him. Haines and McEntyre had already written some very successful beginning band method books and they wanted to follow up with an updated version of the Fussell Book (Exercises For Ensemble Drill, 1985). They wanted Garner to do something on intonation. He states:

“Again, it… really didn’t hold much appeal for me, but they are both good friends and I said sure. But then as we got involved in it, I got more and more and more involved… in not just the intonation part, but all of it. And so, that’s how that came about.”

Garner’s professional interests seem have always been very focused on teaching and working as hard as possible for the students who were currently in his ensemble. In addition to having little interest in publications, he had even less interest in serving as an officer of a professional organization. In regards to holding an office in an organization such as TMEA, TBA, or CBDNA he states, “I got a few inquiries about that but I never sought that, and as a matter of fact, I avoided it.” In some ways he does wish that he had attended more CBDNA meetings. He states:

“I wish I had been more active in that. The only times I ever went is when we played. But you know, WT wouldn’t pay for it. I was raising three kids on a single income. My wife was a stay at home mom and I couldn’t afford to go off to Madison, Wisconsin or Atlanta or wherever. Take three days out of school, pay for the transportation, pay the room at the hotel and I couldn’t afford to miss three days of school either. So, I just decided, in addition to the monetary considerations, I needed to stay at home and mind the store and do the best job I could there. So, I never did do that and I do somewhat regret that I couldn’t.”

However, upon his retirement he states:

“I told Donnie [Lefevre]—I don’t know if he’s ever even thought about it again, but some of my parting words of advice to him were, and with Ted [Ted Dubois – Dept. Head] present—“You need to be going to CBDNA.”

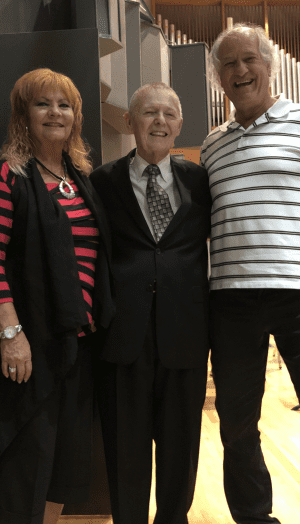

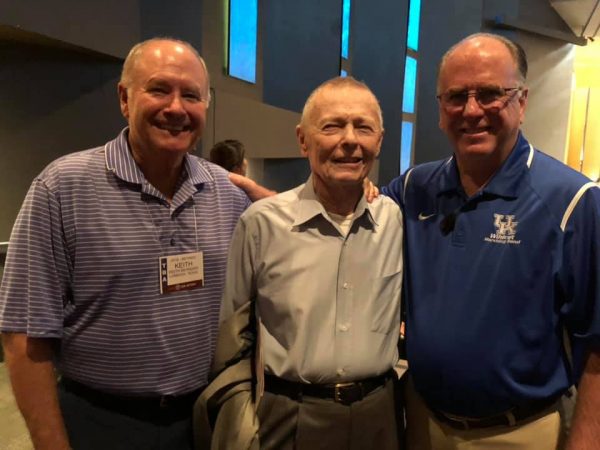

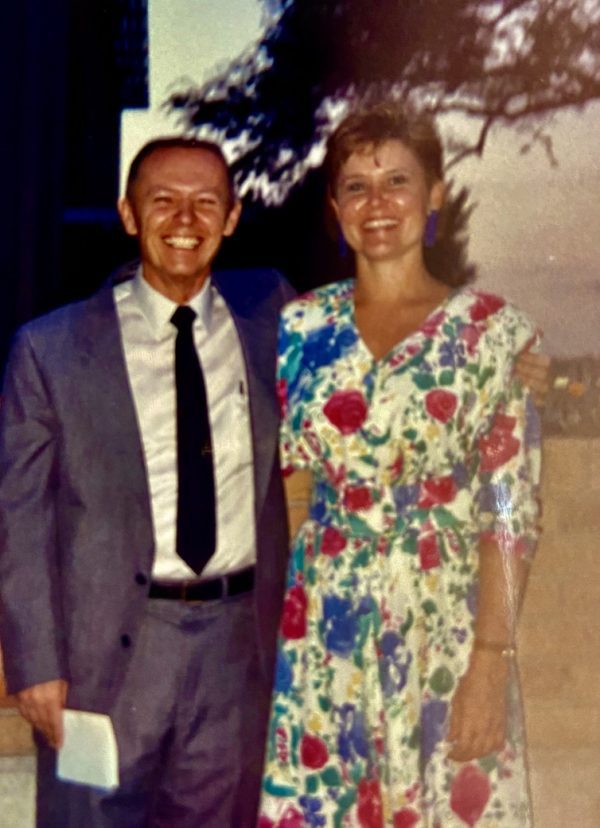

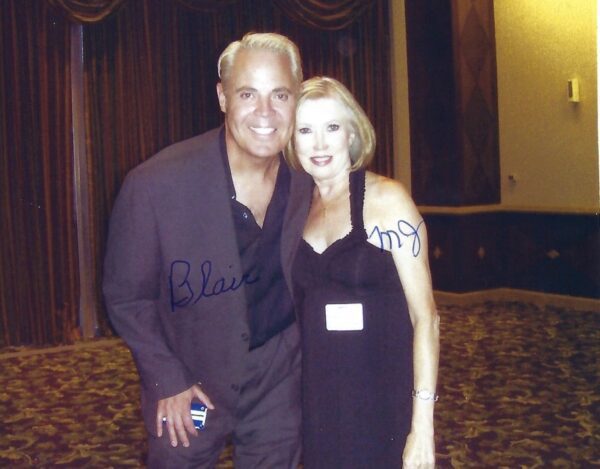

Gary and Mariellen Garner raised three sons who have all achieved successful professional careers. Bryan is one of the world’s leading legal lexicographers, editor of Black’s Law Dictionary, and author of over sixteen books in publication; Brad teaches flute at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music in Ohio and at the Julliard School of Music in New York; and Blair is a radio personality and host of the nationally syndicated After Midnight with Blair Garner. Mariellen passed away in 1994.

All three Garner children have enjoyed remarkable success in their professional careers. When asked about his amazing success, Blair Garner quickly credits his parents, and explains:

“My parents taught us all two very important lessons: First, my father taught us that if we were going to make a mistake, make it as big and loud and hairy as you possibly can. Commit yourself to it. If you're timid, you'll never reach the brass ring. Don't be afraid to fail. Secondly, my mom always told us that we were special. We could do anything we could dream. When you add those two lessons together, the results can be pretty powerful.”

Indeed, Garner was very much committed to being a good husband and father. He tells of a conversation he once had with A. A. Harding the director who organized the first college band in the United States. The conversation had a profound effect on him. Garner describes Harding as a wonderful musician who actually had a degree in engineering rather than music. Garner explains that Harding was a prolific arranger out of necessity, because at that, time there was a great lack of music that was worthy of the band Harding had at Illinois. Harding, and his staff of copyists, regularly worked late into the night completing arrangements for the Illinois band. Garner came to know Harding fairly well. He recalls first meeting Harding his junior year of high school when he was Garner’s judge for a flute solo at the Tri-State Music Festival in Enid, Oklahoma. Years later, Harding and Garner would work together in the summers at the Texas Tech Band Camp. Garner states:

“He remembered me from that [judging] and there was, I think, a certain kinship. Fellow flute players, although I was very much the junior partner there obviously, but I came to know him fairly well and liked him a lot. He was very kind to me and the last conversation I recall having with him there are two vivid recollections I have of it. One was, he had just been made honorary lifetime member of ABA (American Bandmasters Association) and I had read about that in the School Musician. I complimented him on that. He said, “Well, thank you very much, but I’m not sure that that was such a good thing. I’m the third person to be so honored. The first two were John Phillip Sousa and Edwin Franco Goldwin.” And I’ll never forget this phrase, “and they both had the kiss of death on them when they got it.” And, he too had the kiss of death on him, because it wasn’t very long after that that he died. But the important part of that conversation that I wanted to relate was, he said: “You know all those nights I spent up at the Illinois band room working away on those arrangements, it just seemed of transcendent importance to me and in the meantime my wife,” they had one daughter, “my wife died.” And I’ll never forget this either, he said: “and my daughter grew up and I never knew her. And now what do I have to show for it.” I think that’s virtually word for word what he said. Well, it made a profound impression on me.”

At the time Garner and Mariellen were newly married and did not yet have any children. He states:

“So, I resolved that I would never let that happen to me, and I think I fairly well managed to avoid that trap. Not completely… but anyway, between doing everything I was doing that was work related and trying to be a good family man, there was no extra time. There was none.”

Garner has also received numerous awards including the WTAMU Faculty Excellence Award, the WTAMU Alumni Association’s Phoenix Club University Excellence Award, the National Kappa Kappa Psi-Tau Beta Sigma Bohumil Makovsky Award, the National Kappa Kappa Psi Distinguished Service to Music Award, the Texas Bandmaster of the Year Award, and is a 2003 inductee of the Texas Bandmasters Hall of Fame.

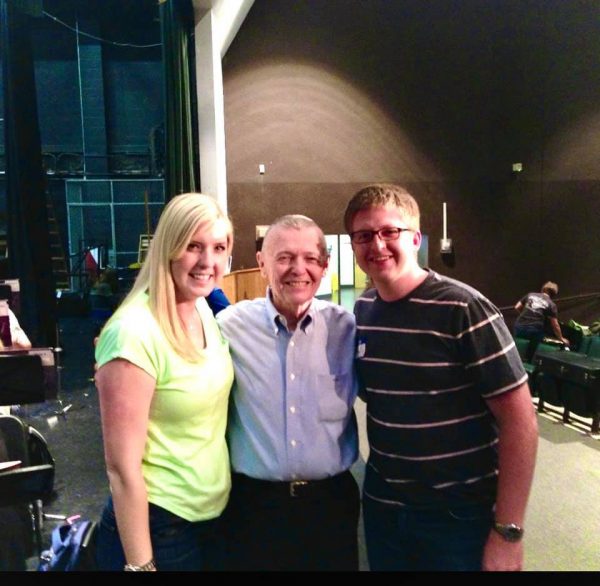

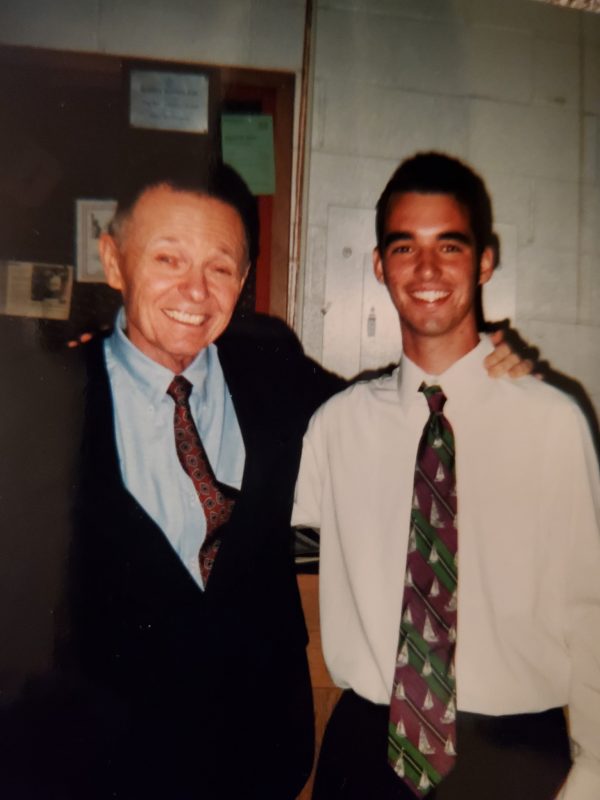

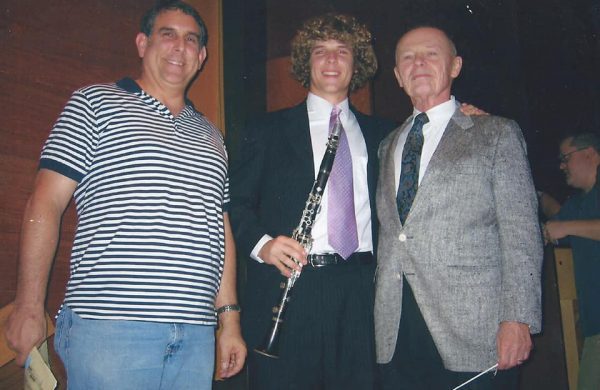

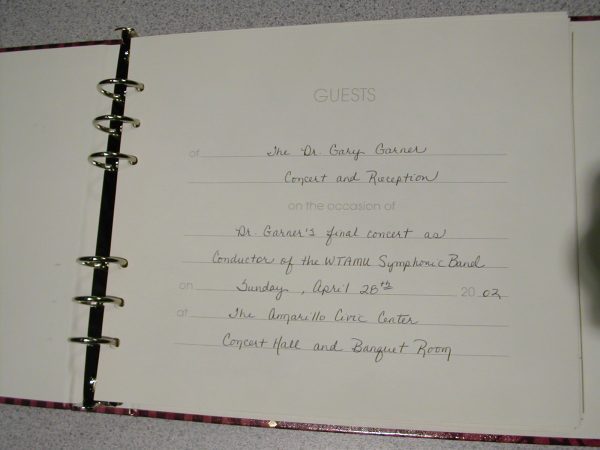

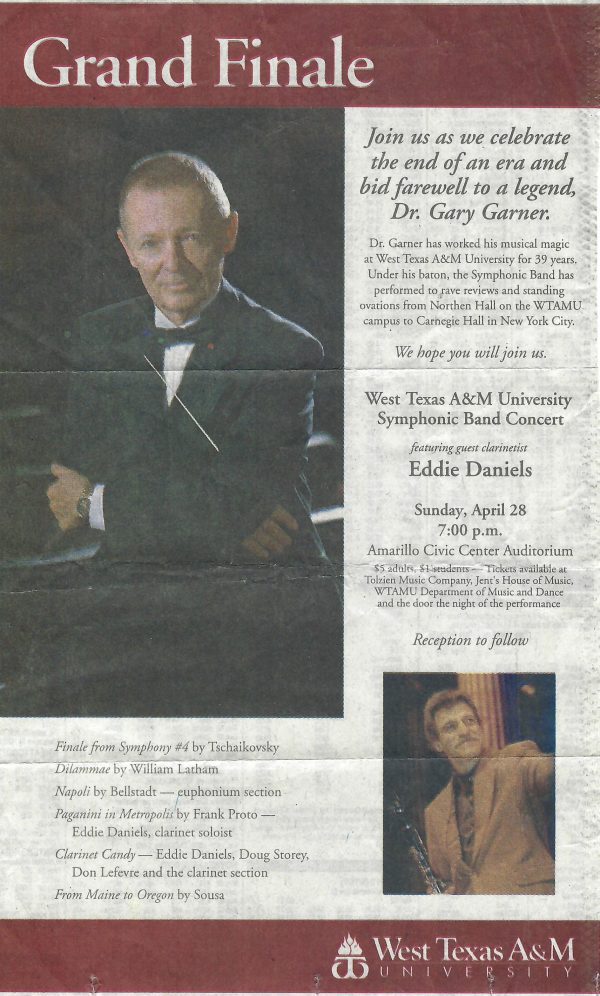

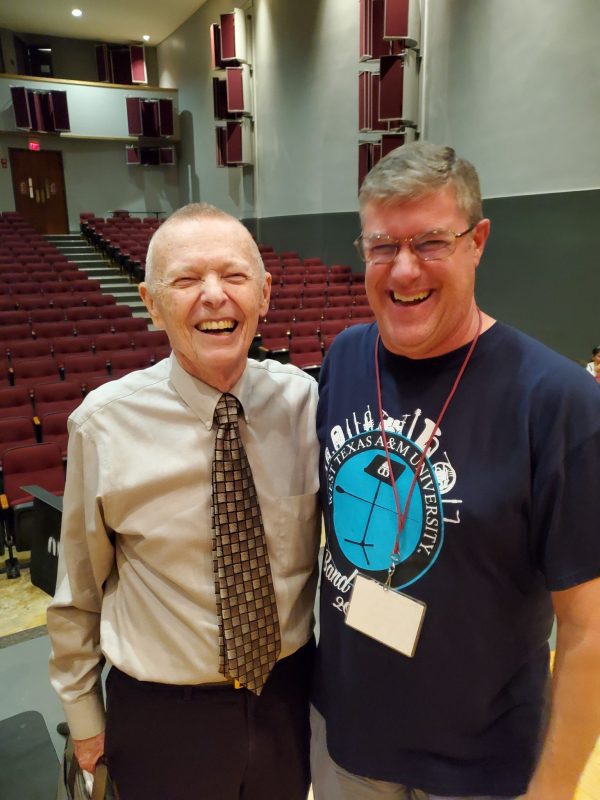

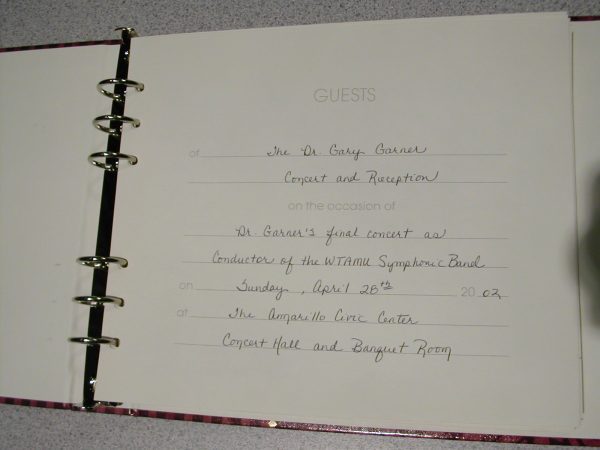

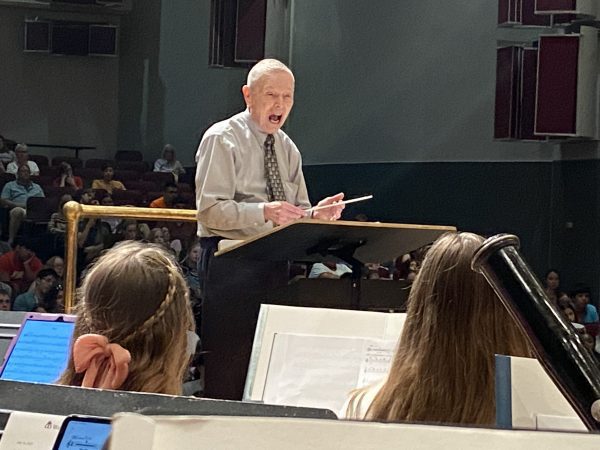

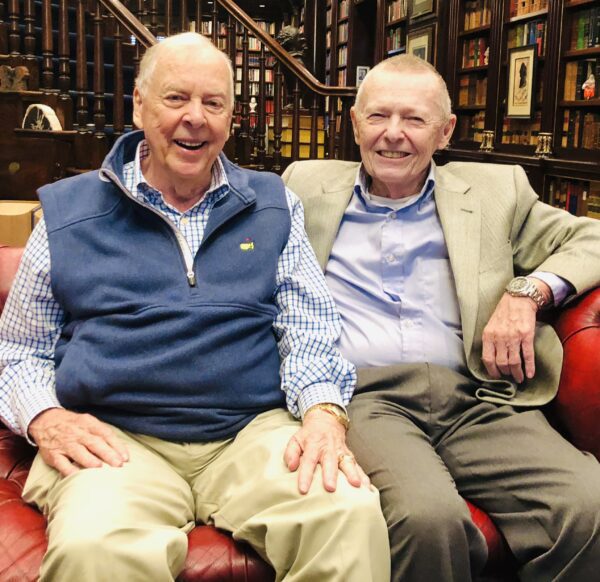

Garner retired in 2002, following a final concert presented at the Amarillo Civic Center Auditorium on Sunday, April 28, 2002. Now at age ninety one, he remains active as a clinician, author, arranger, great friend and mentor.

Alumni Testimonials

Take a look at what some of our alumni have to say! You can use the arrows on the left and right side to navigate through them.

Mobile users can also swipe left and right!

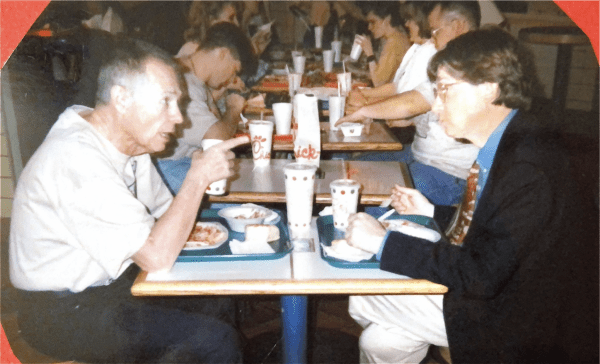

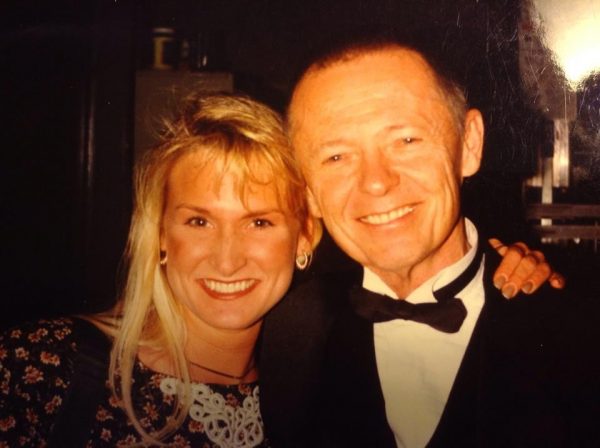

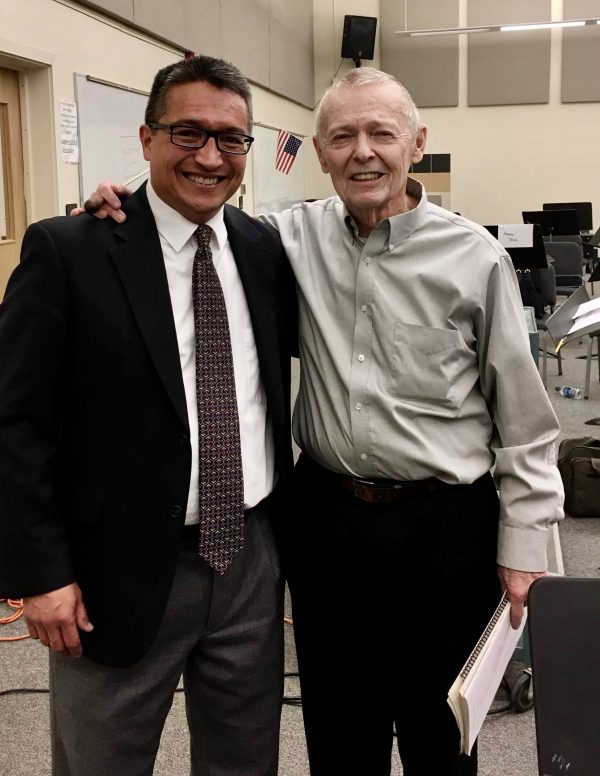

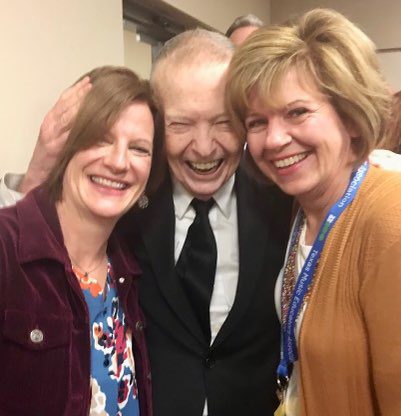

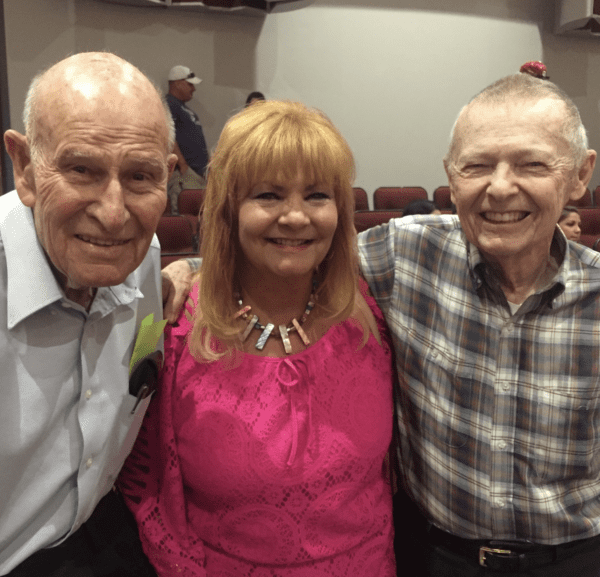

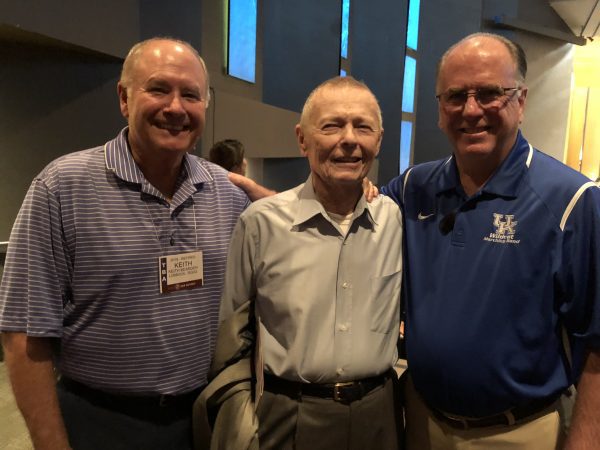

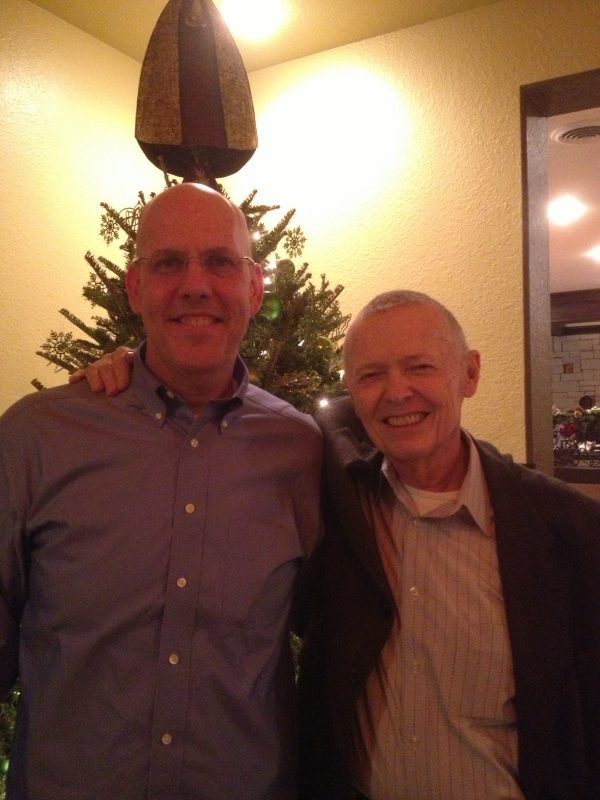

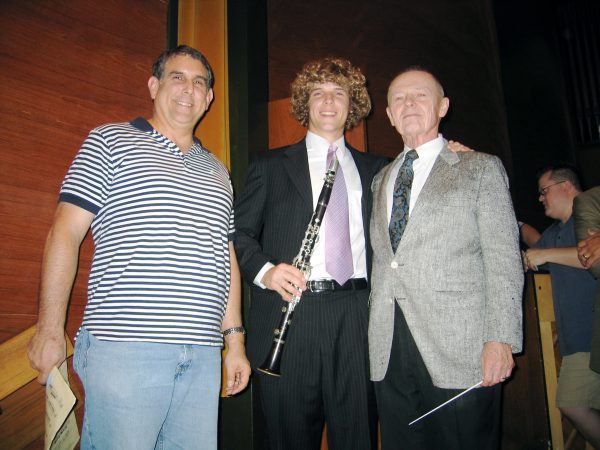

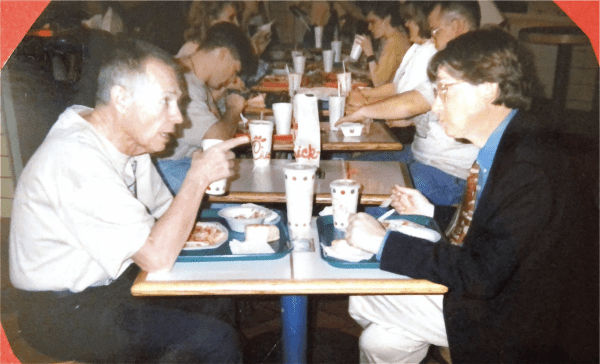

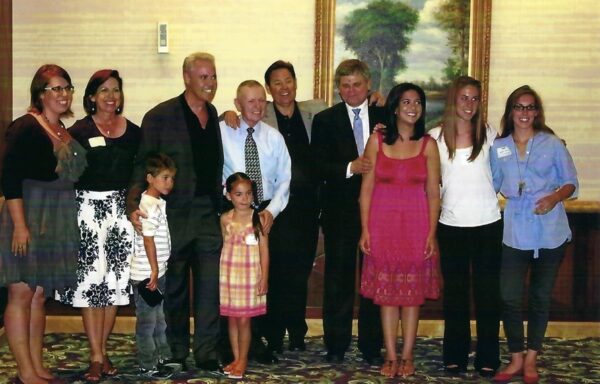

Alumni Tribute Photos

Alumni Tribute Videos

Prologue

Recently, Judy Pierce, a former clarinetist in Dr. Garner's bands, suggested putting together a short poem outlining Dr. Garner's history at West Texas A&M and his impact on the Texas school, music scene. Judy and her husband, Jim, assisted materially in this by helping the writer find public source information on Dr. Garner's band directorship, providing videos of his interaction with his former students, and contributing their own anecdotal memories of the man and his music.

The following rhymed verses are not meant to be a journalistic record of Dr. Garner's time at West Texas A&M formerly West Texas State University but rather give an impressionistic portrayal of how his character positively influenced so many of his students.

The poet has arbitrarily broken the poem into three sections; the first speaking mainly of the professor and the bands, the second recounting his own memories of personal contacts between him and a few of his students, and the third positing some possible basis for the magic in his music.

Jimt

Epilogue

My deepest appreciation goes to Jimt for his time in creating a poem projecting the essence of Dr. Garner. This book was made to honor Dr. Gary Garner to express how his leadership has influenced every student touched in his teaching career. Photos have been scanned from 1967 to 1970 WTSU annuals or the WTSU campus newspaper from that era and my personal photos. Photos of Dr. Garner and his sons were taken from the Internet with public access. It is not intended to be sold for profit.

Jimt writes poetry about significant events and people and has a website where his poetry is shared. He wrote such a poem about my husband and me playing golf and our personalities both on and off the course.

Over the years, Jimt has listened to my husband and myself tell stories about the West Texas band alumni reunions. He became interested in Dr. Garner and his affiliation with the WT band and his rapport with his students and alumni. Jimt wanted to find out what keeps bringing the alumni back to share events, a day, or even a few hours with this professor who has had such an impact on so many lives. While we remember it differently, Jimt brought up the idea of writing about Dr. Garner which I quickly embraced and became engaged in researching this bandmaster’s career.

This poem came about with Jimt’s unique, creative style as we shared information about Dr. Garner. Jimt decided on the topics that interested him most to write about. I left this up to him as he wrote from his perspective what he took from our stories and his interpretation of those stories.

Judy Mercer Pierce –Class of 1970

Dr. Garner, it is truly impossible to express adequately how much I love and respect you! What a blessing it was for me to have had the honor of being in your band for four years.

The memories I have are wonderful. Thank you for helping me on my bass clarinet and for always encouraging me with you kind words! I am pretty sure all who were ever in your band

feel exactly as I do. Thank you from the bottom of my heart!! Sharon Goode Guenat

First of all, I would like to express how wonderful this Tribute to Dr. Gary Garner section of the website is. Great job to Charles, Don, and everyone for contributing.

Dr. Garner,

Happy Birthday, Dear Mentor and inspirator. You have inspired and led so many through the years with your professionalism, your expectations for each band member, and sense of humor bringing us together as a family. One of the reasons I decided to attend WTSU was because of you. During my high school years when you conducted clinics with the Pampa High School band, your work ethic influenced me to be the best I could be and contributed to my making All-State and making music such an important part of my life.

You and Mrs. Garner were wonderful father and mother figures to all the band members even though you weren’t that much older than us. That sense of family keeps us coming back to share a very treasured time in our lives. You will always own a piece of my heart.

– Judy Mercer Pierce